Despite a recent legal victory, thousands of California farm workers await another legal decision on the fate of their votes, by the state agency they petitioned to hold the election.

The Agricultural Labor Relations Board is mandated to protect the rights of California farm workers. However, the ALRB instead waged a systematic campaign against thousands of farm workers in 2013 to prevent them from voting to de-certify the United Farm Workers union at Gerawan Farming, one of the nation’s largest family-owned fruit producers.

Court documents, legal testimony, and sworn statements demonstrate a pattern of voter intimidation, harassment, last-minute rule changing, and other tactics to disenfranchise the Latino farm workers of Gerawan. Legal documents show that the ALRB general counsel and the Visalia-based regional director orchestrated a concerted effort to manipulate the votes of thousands of laborers at Gerawan Farming.

ALRB Lawyer Orchestrated Intimidation, Segregation

ALRB General Counsel Sylvia Torres-Guillén led the agency’s effort to prevent the workers’ vote from taking place at all by disqualifying thousands of signatures gather by the workers. Then, when overruled by the three-person board in Sacramento, Torres-Guillén orchestrated the operation to discourage workers from voting. She was on-site when Silas Shawver, ALRB Regional Director for the Visalia area, supervised the segregation of hundreds of voters and the intimidation of hundreds more.

Must Have ID To Vote

After the ALRB board countermanded Torres-Guillén and ordered the election to take place on November 5, 2013, Torres-Guillén, Shawver, and UFW organizers worked feverishly to concoct reasons for segregating workers from crews known to support de-certification. They selected leaders of crews, known as “crew bosses,” alleged by the UFW to be anti-union, and singled out all of their members for questioning and impounded their ballots.

Shawver led a pre-election briefing for the workers on November 4, so that they would understand the procedure and to bring with them some form of identification. If they did not have a government-issued photo I.D., he said, they could prove their identities with a Gerawan wage check stub bearing their names, that would be cross-referenced on the voter lists.

Changing the rules

Sworn statements from scores of laborers and other documents confirm that Shawver changed the rules on voting day.

Minutes before midnight, at 11:54 p.m. on the eve of the election, Shawver officially advised Gerawan and the workers that he ordered that the ballots cast by “several entire crews” to be “segregated,” at the request of the UFW, legal documents show.

The union alleged that Gerawan had fired workers opposed to the union and stuffed the work crews with new employees to vote against the UFW, illegally under the names of the former employees. Although the UFW provided no evidence – before or since – to substantiate the allegations, Torres-Guillén and Shawver accepted the accusations, even though labor standards require probable cause.

The ALRB and UFW team staged an all-nighter to frustrate the election. Shortly before dawn on voting day, Shawver sent a message the employer and employees the names of the crew bosses for the eight crews to be segregated.

With that declaration, Shawver segregated about 800 workers – about 30 percent of the work force, with no basis under ALRB regulations, and no probable cause. “This latest gambit can only be viewed as an effort to sabotage the election,” Gerawan attorney David A. Schwartz said in a November 5 letter to ALRB Executive Secretary J. Antonio Barbosa in Sacramento.

Segregation, California-style

Silvia Lopez, the Gerawan worker who organized the decertification campaign, detected union corruption of the voting process, and feared that Shawver and other ALRB attorneys were rigging the vote in advance.

The ALRB was accepting UFW challenges to the ability of Gerawan voters even before the voting took place. The day before the election, Lopez’s counsel, Anthony Raimondo, warned Shawver that Lopez “objects to the submission of pre-election challenges, as they tend to discourage the participation of those who will be challenged.” She said she saw union corruption at issue. “It is a simple matter in a case such as this for a party, such as the union here, to fabricate claims that call into question the eligibility of groups that they believe will vote against them, and then discourage those groups from participating by letting them know that they will be challenged in advance,” Raimondo told Shawver.

Under ALRB lawyer Torres-Guillén’s personal supervision at the election, 800 workers from the eight targeted crews were physically segregated at the polls in front of the other workers. Rumors spread among the voters that the ALRB was “investigating” them.

“When I arrived at the voting site, the ALRB agent named Silas . . . told us that some of the crews were being challenged,” said a grape-packer named Ana, working in Yard 45. Ana – her surname is legally protected against potential union intimidation – and the rest of her crew took time off to vote as a group.

“I asked why our vote was being challenged. Silas’ tone of voice then changed, and he stated there had been an allegation against the company that people were hired to vote. Silas told us that if the allegation was to be confirmed, that all of the votes for that crew would be thrown away in the trash,” Ana said. “I did not feel good about my vote, because I felt that my vote would be thrown away.”

ALRB employees took their names and placed their ballots into separate yellow envelopes.

“The mass segregation of ballots, based on membership in a crew, is not only a per se illegal basis to challenge eligibility,” attorney Schwartz told ALRB’s Barbosa in a detailed protest. “It is a blatant attempt, orchestrated by the UFW and abetted by the Regional [ALRB] staff, to interfere with a free election, and to send a message to every worker that the Board believes that the voters are unable to exercise their own independent judgment,” he said.

“By relegating some 800 workers to this suspect, second-class category of voters, it sends a message on this election day that the Board’s bias will trump the statutory right of free choice,” Schwartz said. “It threatens to create an atmosphere of coercion and intimidation. The staff conduct amounts to taxpayer-funded voter suppression and intimidation and includes subtle threats about immigration status.”

“By relegating some 800 workers to this suspect, second-class category of voters, it sends a message on this election day that the Board’s bias will trump the statutory right of free choice,” Schwartz said. “It threatens to create an atmosphere of coercion and intimidation. The staff conduct amounts to taxpayer-funded voter suppression and intimidation and includes subtle threats about immigration status.”

“Disenfranchisement tactics of this sort were used by Jim Crow segregationists to intimidate voters, or to deprive them of their unfettered right to vote. Restrictive and arbitrary polling and registration practices designed to delay, obstruct, and discourage voting were but one means. That is what is the effect, and likely the intent, of what is now occurring,” Schwartz continued in his letter. He requested “immediate action by the board.”

Nothing happened.

The ALRB said it would investigate the UFW’s last-minute allegation that Gerawan had replaced the work crews to have anti-union people vote under the names of the workers. Instead, the allegation was used to delay a hearing while the ALRB General Counsel “investigated” – until Torres-Guillén dropped the matter entirely.

Un-announced changes of rules to require voter ID

Before the election, the ALRB said the workers only needed a paycheck stub to establish their identities as Gerawan employees entitled to vote in the decertification election. However, on voting day, Shawver required the farm workers to show government-issued identification cards.

The day before the election, Lopez’s attorney, Anthony Raimondo, wrote Shawver to confirm that the ALRB, Gerawan Farming, and the workers all agreed “that any photo identification or a Gerawan check stub is suitable identification. If a voter presents suitable documentation, and good cause cannot be shown to support a challenge, then the voter should be entitled to vote and should not be subject to challenge.”

But that did not happen.

ALRB traditionally has accepted the reality of agricultural workers not showing identification cards. If ALRB demanded ID for each worker who voted, it would harm the ALRB’s mission to be the workers’ advocate, while undermining the workers, the employers, and the union. With the ALRB insisting on workers showing their IDs at the polling places at Gerawan Farming was an indication that Shawver was intentionally trying to dissuade employees from voting at all in the decertification balloting.

“When I was in line, I overheard the ALRB agents asking the workers if they had their I.D.s in addition to their check stubs,” said a worker named Rigoberto. “I heard other workers commenting that this was an interrogation, and then they left. The workers had no privacy during this process.”

An ALRB agent “asked me for my I.D. in addition to my check stub,” a worker named Maria V. said in a sworn statement.

Raul, a Gerawan worker testified, “The ALRB agents came to speak with us the day before, but they did not tell us we would have to fill out a form. They only told us that if we did not have an I.D. we could use a check stub.” However, he said, the ALRB changed the rules on voting day: “While I was in line, the ALRB agents were asking if workers had their I.D. in addition to their check stub.”

No good cause

ALRB regulations require “good cause,” similar to probable cause, to uphold an objection to a worker from voting. As an example, good cause might be suspicion that an employer replaced an entire work crew with new people operating under the names of former employees still on the payroll list. “

If this allegation has any merit at all, the union should be able to produce at least one individual who is working under a name that is not his or her own, and who was directed to use that name for the purpose of voting,” Lopez’s attorney told Shawver. “Without such evidence, the ALRB should be very hesitant to interrogate or scrutinize agricultural employees about their identities, as such inquiries can raise the specter of immigration concerns, which can chill participation in the process,” Lopez’s attorney said.

Workers recognized ballot problem before the voting began

Worker Silvia Lopez requested at a pre-election conference that the ALRB impound the ballots in Sacramento, with executive secretary Barbosa or with the actual three-person board, rather than allowing custody of the ballots to remain with Shawver, and Torres-Guillén.

“We simply have come too far, and too much has transpired for Ms. Lopez and her co-workers to have any confidence in the integrity of the Visalia Regional Office and the General Counsel,” Lopez’ attorney Raimondo wrote to the ALRB’s Barbosa. “Sadly, the conduct of Mr. Shawver and Ms. Torres-Guillén lead to the inexorable conclusion that there is at least the perception of bias, and very likely actual bias that undermines the functions of the ALRB and the rights protected” by state law. Lopez “humbly requests that the Executive Secretary or the Board itself take custody of the ballots pending post-election litigation. Such action would go a long way towards restoring the workers’ shaken confidence in the agency and this system, and would allow all involved to rest easy that the ballots are in safe custody.”

Barbosa and the board did not take custody of the ballots. Instead, Shawver stored them in a safe in his Visalia office, as Torres-Guillén led the legal proceedings to have them destroyed before they could be counted.

Violation of NLRB procedures

Shawver and Torres-Guillén backed the UFW’s “en masse objections” or “group challenges” of entire groups of voters. The purpose of the objections, made before the election began, was to negate the votes of entire work crews known to have a majority opinion against the UFW. The group challenges had a chilling effect on other voters.

California state law does not stipulate how the ALRB may allow farmworker ballots to be challenged. Since the ALRB was explicitly modeled after the federal government’s National Labor Relations Board, the NLRB’s practices may provide a guide. “The NLRB has long held that each voter’s ballot must be challenged individually when the voter appears at the polls, and a party’s expressed desire to challenge voters en masse made when the polls opened is not sufficient to state a challenge,” Lopez’s lawyer told Shawver in the letter the day before the vote. “The NLRB Case Handling Manual also makes clear that challenges are typically only raised during the voting, at the time that the challenged voter appears to vote.”

Under the NLRB manual, “observers may bring lists of names they intend to challenge, but may not maintain lists of who has or has not voted. NLRB procedures allow parties to note challenges on the eligibility list at the final pre-election check of the list, as long as those challenges are distinguishable from the marks to be made by observer,” Lopez’s lawyer, Anthony Raimondo, told Shawver.

“It appeared to me that something was wrong,” said grape picker Antonio at Ranch 102. “It looked crooked to me.”

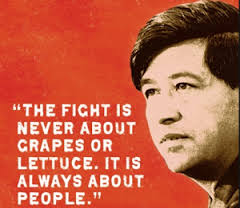

Workers Abandoned by UFW

A state court found that the UFW abandoned the Gerawan workers for nearly 20 years before returning in 2012 to assert control over their contracts. Part of the contract required all workers to pay three percent of their wages to the union, or lose their jobs. Silvia Lopez, a second-generation laborer at Gerawan, led a successful effort to have the ALRB supervise an election to remove the UFW’s claim on their wages.

Gerawan’s large, well-paid workforce represents a cash cow for the UFW, whose worker dues would inject the dying union with millions of dollars a year.